What you’ll learn

This article is Part 1 of the ACL Reconstruction Surgery series, especially for fit, active folks and rock climbers. This covers everything pre-surgery, from graft choice to pre-surgery rehab.

You’re in a Panic and Slightly Depressed

You found out you tore your ACL. You’re a fit, athletic person and the year-plus ACL rehab away from your outlet and hobby is depressing. You’re scouring the web in all your free time, trying to glean any information you can on surgery, graft choices, statistics, and the best possible outcome for back-to-sport.

Fear not. ACL tears are almost exclusive to sports, which means you’re probably athletic and you’re going to be motivated to do physical therapy. Physically, you’ll deal with it. It sucks, but you’re motivated, and you’ll come out stronger.

It Clicks, Pops, Crunches

I was scared sh*tless that I had shredded my whole knee because it made all kinds of noises and pops for a week after I torn my ACL (both times). Turns out I had literally only tore my ACL and everything else was in tact (both times). Calm down, get an MRI, and then deal with it.

What I wish I had known to avoid 2 ACL surgeries

Stress and cortisol wreak havoc on your body healing

So, no panic, no depression. I didn’t manage my emotions well after my 1st ACL surgery. I was in a stressful place at work, I didn’t have my outlet of rock climbing, and in hindsight, my cortisol levels were sky high. My graft hadn’t healed enough at 9mo after my 1st surgery, and what should have been a normal climbing fall resulted in a loud pop and a 2nd surgery.

The mental challenge was immense

Staying away from my love and outlet, while seeing my friends climb, was incredibly hard. Physically, I did stellar, and actually enjoyed PT and strength building.

Hardly anyone is going to understand what you’re going through

Mentally and physically, surgery recovery takes a lot of time and effort. Most won’t understand why you’re not back to sport yet.

See the first article in this series for a survey of [mostly] rock climbers, their graft choice, and recovery timeline. Please also give back by filling out the survey yourself.

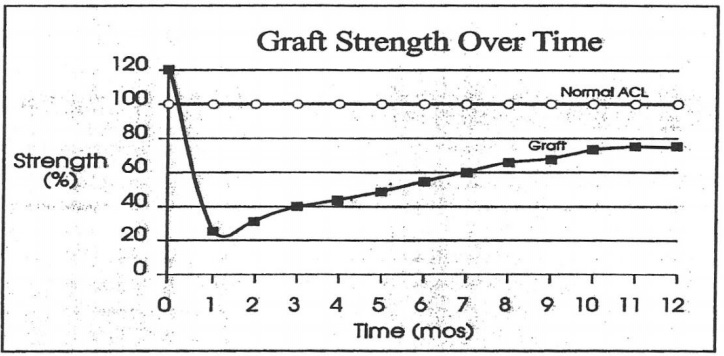

ACL reconstruction takes >1yr to heal, no matter how much you fool yourself into thinking you’re above the curve. Your graft literally goes through necrosis, weakening down to 30% strength, before transforming into a “normal” ligament over 18+ months. No matter how gung ho you are, how strong you think your muscles are, or how good you look, the graft will take time.

I fell into the trap of looking at other professional athletes going back to sport in 6mo. Bouldering is not a normal sport for impact, when you fall 50+ times a workout from 10+ ft. Most all surgeons and PTs won’t understand what bouldering is and quote an earlier back-to-sport than you should.

Surgeon Choice

If your insurance allows, shop around for multiple surgeons. I met with 3 before I settled on one I liked, and it was an obvious choice. You’re essentially interviewing surgeons and they should take time to talk with you and answer your questions. I had one surgeon hand me a stapled stack of papers on graft choices, left the room, and came back 15min later asking if I made a choice on graft yet, without any conversation.

Friends also are great resources to find surgeons. If you’re in the Bay Area in California, contact me for referrals.

ACL Graft Choice

The surgery goes as follows:

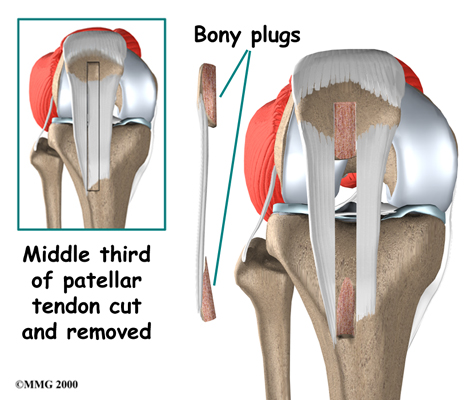

- Your torn ACL will be removed and holes drilled through your tibia and femur (left).

- You choose from different tendon grafts which slowly morph into an Anterior Cruciate Ligament over the next 1+ year. The new graft is strung through the holes in your bone (middle).

- The graft is secured with biodegradable screws (right).

For my 1st surgery, I used a cadaver patella; for my 2nd, I used my own hamstring.

Find out which your surgeon recommends for you, which graft they commonly use on other patients, and compare that against what you think is best for you. I’ve heard surgeons on the West coast tend to favor patella, and East coast tend to prefer hamstring. You should be comfortable with the graft your surgeon recommends and is comfortable with, and that should mesh with what your goals are for the next 50+ years of your life.

Autograft Patella

An autograft patella is your own (auto = yourself) patella tendon, the one that sits in front of the kneecap. They take the middle of it and suture the two sides together.

Autograft Patella: Pros

- Your own tissue, so a quicker healing time than cadaver in the long run.

- Bone plugs are taken on either side (“bone-tendon-bone”). The bone endpoints make it faster to fuse with your own bone in the early months.

- One of the first grafts used for ACLs; your surgeon may have more experience with it.

Autograft Patella: Cons

- Much more quad atrophy.

- High risk for long-term pain kneeling. Not recommended if you do work on the ground or yoga.

- High risk for tendonitis.

- Pain post-surgery in front of knee.

- Early ACL rehab harder because of pain, inability to activate quad, and high likelihood of developing tendinitis if pushed too hard too early.

- My surgeon recommended against autograft patella for women >30yrs old, since he’s seen long-term pain at a much higher rate.

Autograft Patella: My decision

I didn’t use patella either surgery because of the well-documented long-term effects of pain and tendinitis. It seems to be more recommended to young, <25-year-olds. I wanted to be able to be on my knees and do yoga without pain the rest of my life.

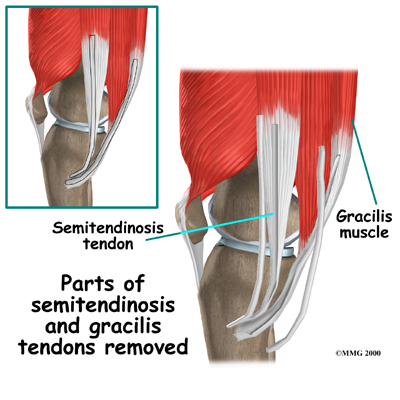

Autograft Hamstring

Did you know you have more hamstring tendons than you need? The big one runs more on the outside of your leg, the biceps femoris, and is left intact. The other smaller ones attach on the inside, the semitendinosis and gracilis. Parts of these “accessory” tendons are taken, braided together, and used for the graft. I used this graft the 2nd time.

You need at least 7mm thickness of hamstring tendon to be harvested for an ACL graft (source). Surgeons typically have a cadaver graft on hand and if your hamstring is too small, they’ll enhance it with a cadaver for a hybrid graft.

Autograft Hamstring: Pros

- Your own tissue, so a quicker healing time than cadaver in the long run.

- Less atrophy in quad compared to patella graft.

- Virtually no long-term side effects if you work on PT to strengthen hamstring after.

Autograft Hamstring: Cons

- Hamstring pain after surgery.

- No bone plugs, so initial fusing to the bone will take 12 weeks vs 8 weeks. Shouldn’t be an issue since you should be taking it easy on your leg for the first 3 months anyways.

- May not be the best choice for athletes like sprinters who need hamstring and glutes.

Autograft Hamstring: My decision

I used my own hamstring for my 2nd surgery and have been very happy. It’s more painful than a cadaver and the first 3 months of recovery much harder, but it feels great after that hurdle. Since my 1st surgery was a cadaver, and that graft failed, my surgeon highly recommended using my own tissue, since my body may not as readily accept foreign tissue. I don’t have any strength deficit compared to my other side.

Autograft Combos

If you choose to use your own tissue, the surgeon will (should) have a cadaver graft ready just in case your tissue isn’t thick enough to use on its own. There’s also combos used of your own grafts, like hamstring-quad combos. Make sure to have the conversation with your surgeon about the if-then waterfall decision tree.

Allograft / Cadaver

Allograft means cadaver. They’re the same grafts as above, or Achilles tendon, or quad tendon, from a cadaver.

Allograft / Cadaver: Pros

- Virtually no pain

- Faster, easier first 3 months of recovery

- The rest of your body is left in tact

- Fastest back to day-to-day life

- Bone plugs for faster fusion to your bone, depending on graft

- Best option for older folks (I’ve heard 45+ years) in terms of collateral healing

Allograft / Cadaver: Cons

- Longer total time back to sport; your body will revascularize foreign tissue slower than its own tissue.

- Potential that your body won’t accept the tissue. Connective tissue takes forever to heal, and if your body is inclined against foreign tissue, it may take a lot longer to transform into a functioning ACL, or never do so completely, and you won’t know–it’ll just be a weak graft until you stress it enough to break again.

- Slight chance of infection, but nearly zero. Tendons are relatively devoid of blood, unlike soft tissue, so risk of infection is very very tiny.

- There’s arguments that they’re weaker than your own grafts since the grafts are irradiated. Technology has improved, and irradiation weakening shouldn’t be a concern.

Allograft / Cadaver: My decision

I opted for cadaver for my 1st surgery. It was a great decision then–I had virtually no pain, I felt I could do more than I was allowed at PT, and back to feeling normal was more like 3 months instead of 6 months with my own hamstring. But I tore this graft after 9 months, even though I was stellar with PT and strengthening.

I caution that if you opt for cadaver, you need to be self-diligent to not push it too fast too early. This graft will feel the best, and you leave your other tissues in tact. Your soft tissue muscles will be ready early, but the graft, which you can’t feel, will take >1 year to heal to back-to-sport.

Pre-ACL Surgery Physical Therapy

Your inclination is to get the surgery as fast as humanly possible. I highly recommend doing PT before your surgery. I didn’t for my 1st surgery, and did nearly 3 months of PT before my 2nd surgery, and the difference was remarkable. You’ll make up the time in recovery.

It’s like going from 0-60mph from a dead stop vs from starting at 10mph: you’ll come out ahead if you prep before.

Right now, your knee is likely swollen and the injured side cramped–your body is literally physically preventing you from using it until it heals. You probably feel like you lost stability (imagine that, a whole ligament gone!). There’s going to be atrophy already. Running into surgery immediately is another huge trauma that will compound the initial injury.

Your PT is just as important as the surgeon choice. You want a PT who will get you back to your sport, not just back to doing laundry at home. I recommend looking for a PT that also touts sports rehab. If you’re in the Bay Area in California, contact me at patchworkandpebbles@gmail.com for referrals.

Fun-ish Facts

- ACL reconstruction is at best 95% successful and there’s 200k surgeries done a year in the US. Most ACL injuries happen in athletes who are at a much higher risk, which confounds the success rate.

- “I see fewer re-tears after 12mo back-to-sport than I do at 9mo; I see fewer re-tears after 18mo than I do after 12mo.” –my surgeon. The precise rate of revascularization (your body taking over the tendon graft tissue and making it a ligament) is unknown–there’s no biopsies done on knees post-surgery. But it’s much longer than professional athletes you see going back to sport at 6 months.

- The graft is weaker than your own ACL, down to 30% of its full strength and builds slowly back, starting at month 2. Over at least 18 months, it’ll get stronger.

- Normal ACLs can take ~2000N of force (~= 450lbs) to tear. It’s unclear how non-contact movement like jumping or planting a foot in soccer to kick can tear the ACL without outside factors.

- Women are at higher risk for ACL tears than men. A survey of NCAA athletes showed 2-3x more ACL injuries for women than men.

- Theories for why women are at higher risk include hormonal changes (ligament laxity increases with estrogen), anatomy (wider hips increase the angle of the femur to knee), biomechanic (women tend to be stiffer when moving rather than absorbing impact), a smaller femoral notch (where the ACL goes through the femur), and relatively stronger quads than hamstrings (hamstrings help compensate for ACL function the most).

→ Explore more articles in Climbing, Fitness, ACL